Nidhi is one of the very few stand-up comedians who are both female and disabled.

Mumbai may not be fully accessible but the people, their energy, never made me feel alone or isolated.

This city gave me stories and experiences which I decided to take to the stage and make people laugh for a bigger change."

Nidhi Goyal, 36

At the age of 30, she started doing comedy to challenge people’s views about her disability and gender.

India’s invisible minority

Out of India’s 1.3 billion people, 27 million are officially recognised as disabled. And even though that’s more than the entire population of Australia, India’s numbers are incomplete.

India doesn’t count disabilities related to age or disease. Also, there is an immense stigma around disclosing one’s disability, and census workers frequently omit the disability question during interviews. So, the percentage of people with disabilities in India (2%) is massively underreported when compared with places like Nigeria (13%) and the US (26%).

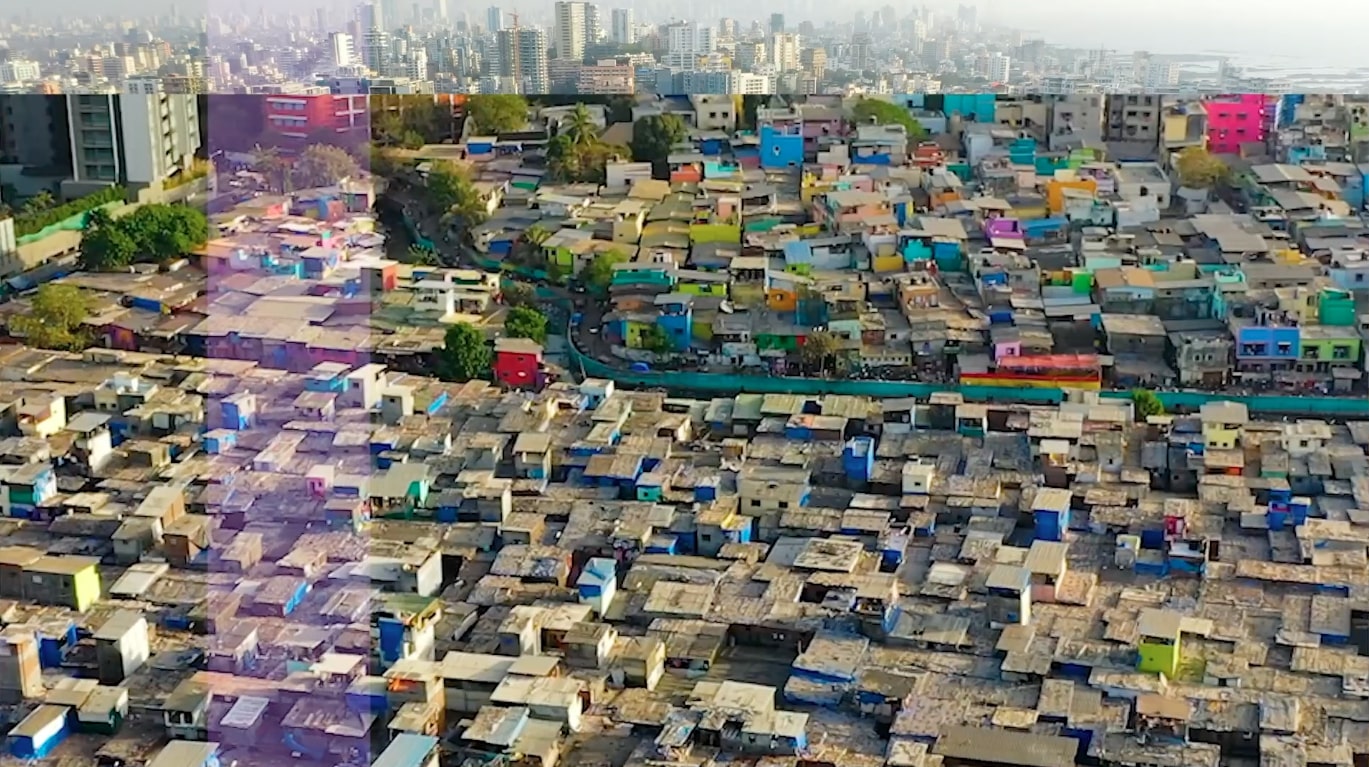

In Mumbai, India’s financial and entertainment capital, the discrepancies are even worse. For example, the government’s number of disabled residents in a poor area with slums called M-East is nearly seven times lower than reported by an Indian NGO.

Nidhi wanted to be a portrait painter since she was young.

But when she started losing sight at the age of 15 because of an irreversible degenerative progressive disorder, she had to find a new career.

Mumbai is considered a walkable city. But for the visually and hearing impaired, navigating Mumbai streets is difficult—there are very few beepers or Braille signs.

Infrastructure and access to public spaces remain woefully inadequate. Even crucial places like railway stations are not disabled-friendly.

The government audited 53 institutes and buildings, including hospitals, educational institutes, administrative offices and police stations in Mumbai. They found that 96% didn't have an accessible toilet for disabled people and 80% didn't have ramps for wheelchair access.

Public transport for all?

Overcrowding, flooding and a collapsing infrastructure have made it incredibly hard for people with disabilities to access Mumbai’s public transport system.

Opened in 1853, the local train network in Mumbai is the oldest in Asia. With many interconnected train lines and over 100 stations, it is fittingly called the lifeline of the city. Trains run nearly 24 hours a day at intervals of 2-3 minutes.

- Many stations have ramps for those with locomotor disabilities, but the incline can be steep or, like in the super busy Dadar East station, the ramp exists to take people up the foot overbridge, but is missing on the other side to take them down to the train platform. Assistance is almost always required.

- Stations are overcrowded, particularly during rush hour. This means getting to platforms, even with assistance, is challenging.

- Based on accounts of visually impaired people, stations with escalators often lack tactile floor markings that lead those with visual impairment towards the escalators, nor are there audio alerts to warn someone that the end of the escalator is approaching.

- Special compartments reserved for people with disabilities are usually filled with regular commuters, and there have been instances of harassment. Also there are no 24-hour security personnel in these compartments.

- During the monsoon season in Mumbai (roughly June-September), flooding and a collapsing infrastructure have made the local train network difficult and dangerous to access for those with disabilities.

- The gaps between the train and the platform are dangerously wide. In 2018, Western Railways raised the height of all its platforms to 900mm to prevent accidents. But the gaps along the harbour and central lines remain as wide as before.

Mumbai’s public bus system run by the Brihanmumbai Electricity Supply and Transport (BEST), is one of the most well-connected bus systems in India, running more than 400 routes across the city. Despite having reserved seats for both women and people with disabilities, less than 7% of public buses in the country are fully accessible to wheelchair users.

- People with disabilities report that drivers, conductors and other BEST employees are inadequately trained in assisting them.

- Pavements leading to bus stations are filled with cracks and often have high kerbs with no ramps. It is nearly impossible for wheelchair users and others with physical disabilities to reach bus stops.

- Overcrowding means buses do not always have enough space for those using wheelchairs, or needing assistance. On average, nearly 2.4 million passengers travel by BEST buses daily.

- In 2016, Mumbai added 25 low-floor buses to their existing fleet. This wasn’t advertised, so a lack of awareness led to low ridership and eventually caused the city to discontinue the service. Since 2020, the government has procured dozens of new electric buses that provide wheelchair access.

- During the monsoons, commuting to bus stations becomes even more difficult owing to flooding in the city.

- Buses do not guarantee seamless connectivity. That means the commute to and from the stops needs to be arranged by disabled people themselves.

Another heritage marker in the city are the kaali-peeli (black and yellow) taxis that charge by distance travelled. Similar in colour, but functioning only in the suburbs, are the cheaper auto rickshaws. Big private players such as OlaCabs and Uber are growing in popularity.

- Cabs and rickshaws are an expensive mode of daily transport for working class people.

- Drivers and other workers employed with taxi services are not adequately trained to assist people with disabilities.

- It is common for drivers to refuse rides based on the fare or destination. So it becomes an added challenge if you need assistance from the drivers.

- This is a particularly common practice during the monsoon, which in turn means that commuters need to wait in the rain for a long time for a cab.

- It is difficult for people with disabilities to hail taxis or rickshaws on busy streets.

- App-based car services are still more expensive and remain largely for the privileged. They are inaccessible to those without smartphones.

In 2017, Nidhi founded Rising Flame, a non-profit that advocates for the rights of people with disabilities.

Nidhi’s activism focuses on women and young people. She is also an adviser to UN women.

Many women living with blindness will report that they have either been groped, harassed, pulled or had their agency taken away while a stranger is supporting them, all in the guise of, at least we’re helping you."

Increasing accessibility through innovation

In 2019, myUDAAN app, India’s first free wheelchair service, was started by Ravidra Singh, who is a paraplegic. Due to the government’s inaction, several apps and start-ups are tackling the lack of accessibility in Mumbai.

Wheelchair taxi and ambulance services like MobiCab and EzyMov are also available for disabled people. However, due to their price and lack of awareness, it’s only the privileged who have access to them.

Poor Indians and Dalits are doubly marginalised

Among disabled Indians between the ages of 15-59, 74% are unemployed or marginal workers. One-third of children with disabilities are out of school.

In the city of Mumbai (excluding the metro areas), nearly half of the population of 12 million lives in slums. Here, the high population density, limited infrastructure, poor sanitation and other shortfalls have led to a growing but largely ignored disability crisis.

Caste hierarchies remain rigid in India. Dalits, who belong to the lowest caste, are nearly 30% more likely to be disabled than upper castes. They are also more likely to have severe forms of disabilities and to acquire them at a young age.

RPwD Act passed but not implemented

While India has one of the most progressive disability policy frameworks in the developing world, implementation is poor. The Rights of Persons with Disabilities Act (RPwD Act) was passed in 2016.

Under the act, the number of recognised disability conditions was increased from seven to 21. People with at least 40% of a disability are entitled to certain benefits such as reservations in education and employment, preference in government schemes, etc. However, disabled people in Mumbai are still waiting for these and other provisions.

In 2015, the Modi government launched the Accessible India Campaign. The campaign’s aim was to make at least 50% of government buildings accessible to people with disabilities in each state capital, and 25% public transport vehicles accessible by 2018. However, by then only 3% of buildings and as of 2020, less than 7% of public buses became fully accessible to wheelchair users in the country.

When disabled women stand up [on stage], they have to pause and acknowledge that disabled women, too, have a voice, they also exist."